Corner of Essex and Summer Streets — Open to the public A new add on for this article Congrads to Bonnie Hurd Smith!

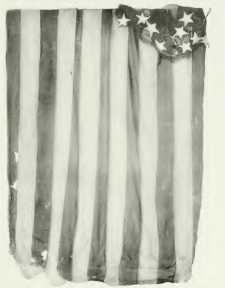

In 1824, a group of “Salem girls” presented twenty-one-year-old William Driver of Salem, Massachusetts, with a massive ship’s flag in honor of his recent appointment as a master mariner. The flag’s blue field contained twenty-four stars, one for each state, and a ship’s anchor in one corner. Organized by Driver’s mother, Ruth Metcalf Driver, the girls were proud of William Driver’s rapid rise in Salem’s lucrative maritime trade since he had first apprenticed as a blacksmith’s assistant and cabin boy. Eight years later, Driver’s employers gave him his own command, the Charles Doggett. Captain Driver joined the ranks of the Salem sailors who circled the globe—so much so that some people thought “Salem” was a country!

Captain Driver proudly displayed Old Glory from the Doggett’s main mast, writing years later, "[It] has ever been my staunch companion and protection … Savages and heathens, lowly and oppressed, hailed and welcomed it at the far end of the wide world. Then, why should it not be called Old Glory?" Over the years, colorful stories have been told about the naming of “Old Glory,” but Driver’s simple words put an end to grander accounts. The flag, and its owner, simply represented the "glory" of American enterprise and independent spirit.

Driver’s career at sea took him to India, China, New Zealand, and Tahiti where he rescued the mutineers of the British ship Bounty who were stranded there. He returned them to their native Pitcairn Island. He also returned to Salem repeatedly with valuable cargoes, so much so that he was able to retire to Nashville, Tennessee in 1838. There, he married his second wife, Sarah Jane Parks. His first wife, Martha Silsbee Babbage of Salem, had died the previous year.

Nashville , where the mystery begins

In Nashville, Captain Driver proudly displayed Old Glory on holidays and for special occasions, including when President Lincoln was elected. But once war between North and South erupted, Driver knew he had to hide his symbol of Northern influence before Confederate troops could find and destroy it—which they attempted to do. Driver’s daughters, and two neighbor girls, sewed Old Glory into a coverlet. The troops never found it! And when Nashville was liberated by Union troops, Driver quickly tore Old Glory from its hiding place and hoisted it above the State House to the delight of Nashville residents.

That night, due to heavy winds, Driver removed his old flag and replaced it with another. And that’s where the confusion begins. What people thought was Old Glory disappeared. Did it accompany the Ohio regiment that liberated Nashville? Was it cut up into pieces for souvenirs like other Civil War flags? All of these stories, and more, were told and passed down through the generations. In fact, Old Glory was safely tucked away in a trunk in Captain Driver’s home. He eventually gave it to his daughter Mary Jane, who took it with her to Utah when she married. A second Driver flag was draped over his coffin when Captain Driver died in 1886. A third flag, known as the family’s “Merino flag,” seems to have found its way North.

Falsehoods

In Salem, Driver’s daughter by his first marriage, Harriet Cooke, was busy making herself into the family historian and ingratiating herself with the prestigious Essex Institute (today, the Peabody Essex Museum). She published a Driver family genealogy, in which she neglected to include Mary Jane Driver Roland, her half-sister in Utah! She also presented the Essex Institute with an old flag, claiming that it was Old Glory. Why would they doubt her? And thus ensued a family feud.

Family feud

Mary Jane learned of her sister’s activities and was furious. She had depositions and photographs taken, and she presented the real Old Glory to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Now, the arguing became institutional as both the Essex Institute and Smithsonian believed they had the real thing. Eventually, the Essex Institute was convinced of the authenticity of the flag in Washington. They even offered to send the Smithsonian the “phony” flag in their possession! The Smithsonian politely declined.

Today

To this day, the Peabody Essex Museum receives inquiries about Old Glory. People are still convinced they own pieces of Old Glory, which they do not. The museum’s card catalog reflects many such gifts. All of them are false! Others are convinced the museum owns Old Glory intact, which they do not.

The real Old Glory, a symbol of American enterprise and independent spirit and not a military flag, is proudly on display—in its entirety—at the Smithsonian Institution. A special flagpole stands over Captain Driver’s gravesite in Nashville, flying the colors day, and also by night under a spotlight. In Salem, a small pocket park with a flagpole and flag is named for him in the McIntire Historic District.

Sources

• Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum

• Ohio Historical Society

• Nashville Historical Society and cemetery

• Armed Forces History Department, Smithsonian Institution

see also Rainy Mountains blog

No comments:

Post a Comment